People exposing abuses remain unprotected while most EU countries miss deadline for transposing EU directive on whistleblowing

By Ida Nowers (Whistleblowing International Network), Marie Terracol (Transparency International) and with thanks to the Country Editors of the EU Whistleblowing Monitor.

Whistleblowing is one of the most effective ways to detect and prevent harms. Still, only

47 per cent of European citizens feel they can safely report corruption, with 45 per cent fearing reprisals for speaking up. Far too often, those who witness malpractice are not empowered to say something, and when they do, face personal, professional or legal attacks, harming their mental and even physical well-being. Robust legislation is key to protect individuals who blow the whistle and ensure that the wrongdoing they report is addressed. In 2019, the European Union drove forward international standards by adopting a directive on whistleblower protection. It included ground-breaking provisions to improve weaknesses and fill important gaps in protection across EU countries. It gave the 27 EU Member States two years to "transpose” it into their national law. Today, 17 December 2021, is the deadline.

Missing the finish Line

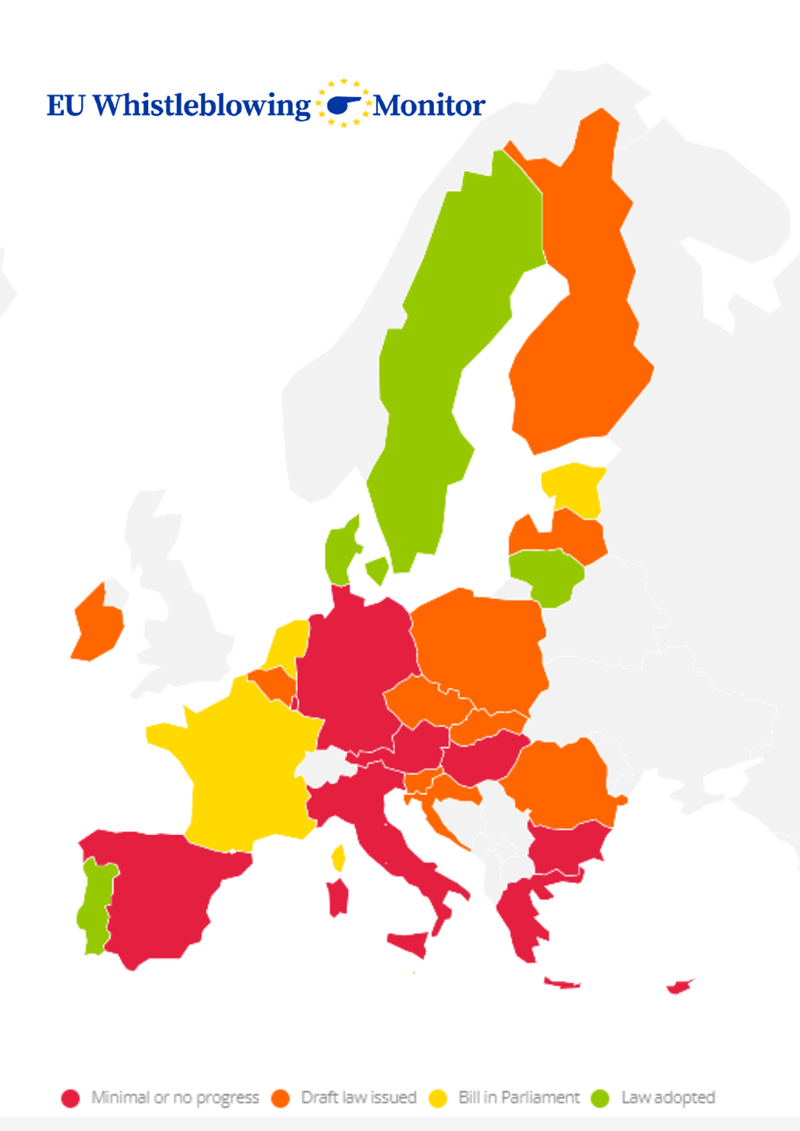

Transparency International and the Whistleblowing International Network have closely monitored the transposition process across all 27 Member States since 2019. In March 2021, we published a

report where we found that two-thirds (18) of member states had not started or had made minimal progress towards implementing the directive. Today, the day of the official deadline for transposition, we find that most EU countries have failed to meet the European deadline to improve their national whistleblower protection framework.

According to our information, of the 27 EU Member States,

only five countries have adopted new whistleblower protection legislation to transpose the directive – Denmark (in June), Sweden (in September), Portugal (in November),

[1] Malta and Lithuania (this week).

Bills are being discussed in Parliaments in three countries – France, the Netherlands, and now Estonia.

Eleven additional countries have draft laws – Belgium (limited to private sector), Croatia, Czech Republic

[2], Finland, Ireland

[3], Latvia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and, just last week, Slovenia. In the remaining nine countries, draft laws have yet to be shared outside government.

While delays in implementing EU directives is not uncommon, the question remains about whether EU countries are taking whistleblower protection seriously. In this case, delays in legislation, in practice, can translate into retaliation against those who speak out. Whistleblowers remain unprotected and wrongdoing that

threaten lives,

the planet or much

needed public funds remains hidden because those who could have spoken up fear to do so.

Lack of transparency and participation

Meeting the deadline for transposition is important but should not be at the cost of a transparent and inclusive process - it is about quality over speed. In

Greece, for instance, where the process in lagging behind, the government has refused to share information about the work of the committee in charge of drafting the law, both in response to freedom of information request by CSOs and to a question filed by 48 members of Parliament.

In Malta, a bill was introduced in Parliament to amend the current whistleblowing legal framework without circulating a draft or consulting with stakeholders, and just a few weeks later, the Bill was adopted, having been rushed through, to

much concern from Civil Society. The lack of consultation when adopting the current whistleblowing legal framework had already resulted in unworkable provisions.

In the

Netherlands, despite a public consultation, the government declined to revise the draft to reflect the recommendations. They argued it was “unfortunately impossible” given the tight timeline. The bill, now before the Parliament, is still heavily criticised by most stakeholders and experts, from CSOs and academia to the Council of State, by both employers' and employees' organisations, as well as by several members of Parliaments, who have asked the government to withdraw the bill and review it.

What might appear a time saver now will have a cost later, when whistleblowers find out the hard way that loopholes undermine their protection, and the law does not fulfil its objectives.

Meaningful consultation with a wide range of stakeholders, including practitioners who have experience working with whistleblowers, such as civil society organisations, trade unions, employer associations and journalists associations – will ensure that the legislation benefit from a wide range of expertise and takes into account the challenges and needs of all those affected by the reform.

Now's the time to transpose properly

It is not yet possible to classify any country as having transposed the directive. Adopting a law is only one step. Often, the law does not enter into force immediately, and further regulations and administrative provisions will be needed. In addition, each Member State must report on the work done to the EU Commission who must assess whether the national legal framework is in line with the directive. Countries who fail to comply with the directive’s minimum standards face an infringement procedure and potential financial penalties.

In Portugal, the newly adopted law limits the possibility for whistleblowers to report directly to the authorities. This is plainly not in line with the directive’s requirement in that regard and far from best practice.

In addition, the directive included a non-regression clause, which means that governments cannot use implementing the new rules to reduce the level of protection already afforded by current national provisions – a

cause for concern already for the proposed reform of the Protected Disclosures Act in Ireland.

Going beyond minimum standards

While ground-breaking in many aspects, the whistleblower protection directive still has flaws; the main one being that it only protects individuals who report breaches of EU law in areas listed in the directive. There is some good news there, as several countries have (to varying degrees) heard

Transparency International,

WIN and the

European Commission’s calls to go beyond the minimum standards required by the directive and offer protection to

all whistleblowers speaking up in the public interest. In Denmark and Sweden, the law protects individuals reporting breaches of EU law, but also more generally serious breaches of national law or ‘serious matters’ (in Denmark) and any misconduct in the public interest (in Sweden).

The bill in Estonia includes a very comprehensive and horizontal approach, and the new Government in Germany has

publicly stated its commitment to a broad, legally secure and practicable implementation. We will be vigilant in the coming months to ensure the laws ultimately adopted reflect these promises.

Conversely, the Belgian, Finish and Polish draft laws extend protection to whistleblowers reporting breaches of national law but only in the areas listed in the directive. While it is a welcome step to somewhat broaden coverage as well as avoid unnecessary complexity such a sectoral approach falls short of best practice, and risks leaving many whistleblowers speaking up in the public interest out in the cold or keeping silent.

Croatia, France, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania and Malta seem to maintain their already broad approach in their draft laws. As has the Netherlands, yet the Dutch bill has been

highly criticised for creating a ‘hybrid’ system of parallel external reporting procedures for breaches of EU law and breaches of national law, with different obligations on those handling them. An approach considered unworkable in practice for all those involved.

Whistleblowers across Europe will only be encouraged and supported in speaking up in the public interest if EU governments urgently adopt whistleblowing laws which provide high-level protection, beyond the minimum standards of the directive. Despite the hanging deadline, it is not too late for EU countries to improve the draft laws and bills and prioritise a transparent and inclusive transposition process. Only then can whistleblower protection laws across the EU be fit-for-purpose and live up to the promise of the directive.

[1] This does not necessarily mean that the transposition is complete – often further regulations and administrative provisions will be necessary.

[2] A bill was introduced in Parliament following stakeholder consultation on a draft but was not adopted before parliamentary elections of October 2021. A bill (possibly the same one) will have to be introduced in Parliament again.

[3] The Irish government issued a very detailed draft scheme of the bill.